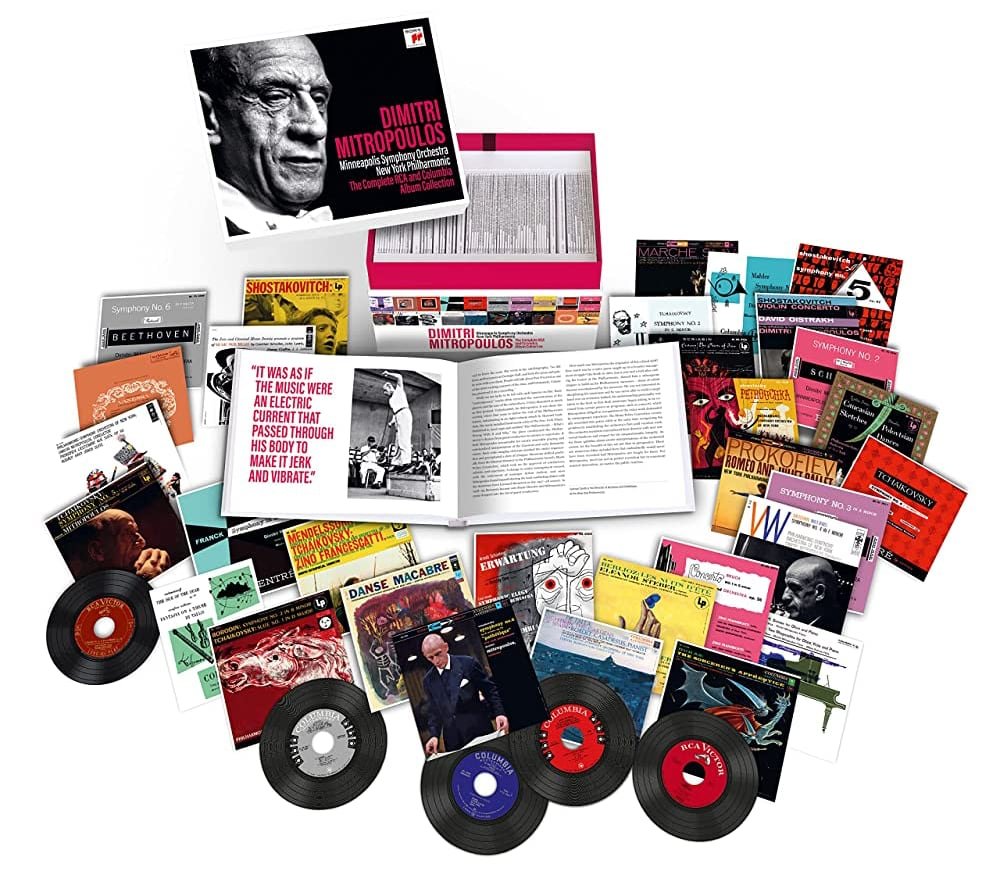

Dimitri Mitropoulos: The Complete RCA & Columbia Album Collection—CD box set

Suppose we allow ourselves to freely associate with what comes to mind when we think of an orchestral conductor. In that case, we can have an image of a person at a podium with an inflated ego, an authoritarian individual, a narcissistic personality, or even a virtuoso that leads us into a euphoric trance with the movement of their hands. In the history of Western classical music, the Toscaninis, Karajans, and Bernsteins of the world make for a larger-than-life image of a master at the podium looking over the brave musicians that carry out their subjective interpretation. There are, however, other not very well know Directors that don't have the personality or need to embrace that “genius” or “authoritarian personality” role associated with them. It appears that Greek conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896 – 1960) was one of these directors. The following is a review of the Dimitri Mitropoulos The Complete RCA and Columbia Album Collection (69 CD box set, released in 2022).

What Comes in the Box

A large and beautifully designed box, with the recordings for RCA and Columbia of his tenure with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra (1937-1949) and the New York Philharmonic (1949-1958). Mitropoulos left a very eclectic and original discography, and he was also a champion of new works, some of which appear in this collection: Milhaud, Barber, Kachaturian, Hindemith, M.Gould, L. Kirchner, Mennin, Lalo, to name a few. It's refreshing to look at these recordings and observe the diversity of sounds that characterized that epoch. Also, there's superb playing by the two orchestras in this box set. I'm getting ahead of myself, but perhaps my favourite recording in this box is Mitropoulos conducting Gunther Schuller and John Lewis compositions for “Music for Brass”, the great Miles Davis, J.J. Johnson, and Joe Wilder appear as soloists, how's that for Mitropoulos' range?

On the box, Mitropoulos' stoic face on the front makes a strong statement. The original cover art of the entire collection adorns the sides of the box. It comes with a beautiful 188-page book with many pictures of the conductor and all the track listings are very well organized by composer, recording, and set number with their release date.

Gabryel Smith (Director of Archives and Exhibitions at the New York Philharmonic) writes the liner notes in essay form (in English, French, and German). While I appreciate the work of Mr. Smith, this very well-written picture of Mitropoulos, there seems to be a disconnection and complete omission of some of the difficulties Mitropoulos experienced during his time at the New York Philharmonic. The moments of discontent that unravelled and limited Mitropoulos' rise were wholly left out, as if omission invited the ugly face of denial. And I won't get into it here, but the orchestra (urged by big names within the Philharmonic) and others devalued his position during his tenure to the point that it ended up with him leaving. If you'd like to read more about it, William R. Trotter's "Priest of the Music: The Life of Dimitri Mitropoulos” tells a fascinating tale.

Dimitri Mitropoulos was born in Athens in 1896, and by fourteen, he was already at the Athens Conservatory studying piano. After returning from studying abroad (in Berlin with Busoni), he became head of the Athens Conservatory Symphony in 1924. By 1930, his concert with the Berlin Philharmonic, where he sat in for an indisposed Egon Petri, playing and directing the German premiere of Prokofiev's Piano Concerto No. 3, propelled Mitropoulos to new heights.

The United States came next for Mitropoulos; he directed the Boston Symphony in 1936 and established himself as the new Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra Director in 1937 (following Ormandy, 1931-1936). Along with his time in Athens, this would be his more secure conducting space, his home. He left in 1949. Mitropoulos first directed the New York Philharmonic in 1940. He was at the baton from 1949 until 1958, sharing duties with Stokowski and Bernstein. Finally, during his last years, at the request of Karajan, he was at Salzburg (1954-1960). He died in 1960 from a heart attack during a rehearsal with the La Scala Orchestra of Mahler's Symphony No. 3.

What to expect from Mitropoulos

First, let me say the remastering of this box is clear and very well done (I have some LPs and 78s of these recordings I compared and can that attest to it), in every-single disc; there's no hum or distortion (especially present on early recordings), or acute volume irregularities. A great job at restorations and transfers, all produced by Robert Russ.

Mitropoulos’ use of his memory and not a score (he was eidetic) explains some of the intensity and emotional connection while conducting, as he had no distractions and knew well what he wanted from each piece. A case in point is his Mahler interpretations. I've mentioned to friends who have asked me about how I started with my "healthy" obsession with Mahler, that it was Leonard Bernstein, Bruno Walter, and even Abbado that tattooed those long Mahlerian melodic jouissance (the Lacanian meaning) and counterpoint disruptions, that appear in my reverie almost daily.

But Jascha Horenstein and Dimitri Mitropoulos made me enjoy and understand Mahler at another level. Different in their execution, both handled the Austrian's oeuvre like a precious jewel. By this, I mean that their interpretation was close to their heart, to who they were. Their performance never lacks the effect on the mind, on the emotional sphere of our subjectivity, tempi, dynamics, and colourful phrasing are always there. Mitropoulos earned the American Mahler Society Medal of Honor in 1940 from the Bruckner Society of America.

I have the Columbia Masterworks set of the 1940 Mahler Symphony No. 1 (in 78 rpm shellac discs) of Mitropoulos with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, and it still has its merits, a specific view of tempi and isolation of instruments that may not be how it's mostly done today. Listening to those shellacs, I wonder how Mahler was being experienced in those days, at the very beginning when his works were being recorded for the first time (since the 1920s, by conductors like Václav Talich, Bruno Walter, Oskar Fried, Carl Schuricht, and Eugene Ormandy).

The highlights: The Complete RCA and Columbia Album Collection

There are too many recordings to choose from in this box. I enjoyed almost everything here, but here are the ones that stood out:

The best of the best, Berg's Wozzeck and Borodin's Symphony No. 2, Manuel de Falla with Robert Casadesus at the piano and the (NY Philharmonic). For me, a lively and beautiful Schumann Third, Franck's Symphony in D Minor is one of the best on record (Minneapolis SO). Several Tchaikovsky symphonies are lovely, his Fourth (Minneapolis SO) and his Pathetique (NY Philharmonic). Jean Casadesus plays Beethoven's Piano Concerto No 3, from 1957 under Mitropoulos and the NY Philharmonic with great expressiveness overall.

Other thoroughly enjoyable recordings in this box: Milhaud and Ravel (Minneapolis SO), Vaughan Williams' Fourth, Hindemith's Sonata for Oboe, and Piano featuring Mitropoulos and oboist Harold Gomberg. Debussy's La Mer with the Philharmonic and Roger Sessions Second are energetic and played amazingly.

Of the operas I found interesting, having never listened to it, Samuel Barber's Vanessa, with Eleanor Steber, Regina Resnik, and Nicolai Gedda. Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera is also in the box, with Marian Anderson making her debut in 1955 with Mitropoulos directing The Met Orchestra and Chorus on both recordings.

Shostakovich's Fifth and Tenth are thrilling, as well as Oistrakh with the NY Philharmonic in Shostakovich's Violin Concerto. Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique is enthralling.

Some recordings are just not for me. The Prokofiev Lieutenant Kijé Suite and Stravinsky's Petroushka lacked lustre, and Beethoven's Pastoral was just good, not great. Above all frustrating is the fact that it only contains one Mahler symphony, mainly since many were recorded with the New York Philharmonic in 1960 (Carnegie Hall) for a festival commemorating Mahler's centenary (on Music & Arts label, 2011 remastered).

Conclusion

Regardless of the contentious nature of his years at the Philharmonic, Mitropoulos certainly had his following, "During the decade before his death in 1960, he was considered in some musical circles to be the equal of Arturo Toscanini and Wilhelm Furtwängler" (John von Rhein, Greek Tragedy, The Chicago Tribune, 1995).

There are several Mitropoulos recordings (not in this box) that give us a glimpse of the Greek Director during live performances (released by Orfeo during his tenure at the Salzburg Festival); as with many great conductors, the Mitropoulos from the studio doesn't compare to his live versions, but don't let this discourage you as the 69 CDs shine a light on the greatness of Dimitri Mitropoulos and are something to be treasured (and owned). On a more social and cultural level, this box is a historical representation of classical music in the mid-Twentieth century classical repertoire, a change in the tides of sound led by the great Greek.

On the last thing about expectations and their complex relationship to our psychology, Gafijvzuc comments: "Expectations respond to the uncertainty of possession. They resonate with anticipation but often are only the fulfillment of disappointment. Always operating under the directive of possibility, expectations can just as quickly undermine it" (from Identity, Aesthetics, and Sound in the Fin de Siécle).

This is the best introduction to Dimitri Mitropoulos. Still, I have another wish. I hope you will look for his live recordings to complement this unique box set.