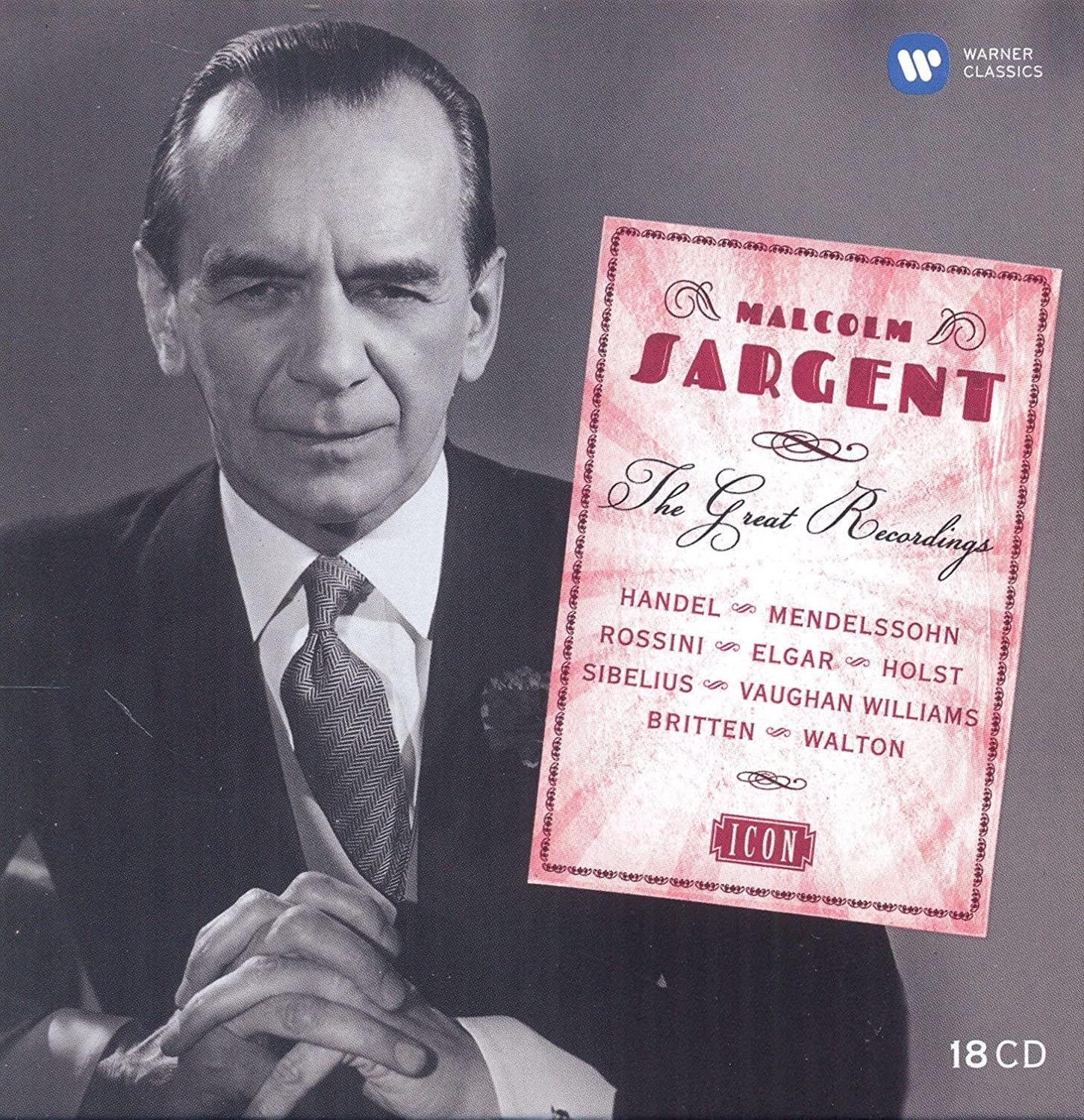

Sir Malcolm Sargent—The one that got away? 18 CD Box Set from Warner Music: The Great Recordings

When discussing the great British conductors of the 20th century one name is consistently missed off the list and examples of his recorded legacy have been difficult to find on CD or even streaming until recently. Sir Malcolm Sargent.

I stumbled across a Warner box set of 18 CDs and realized that I had had many of these performances on disc in the ’70s and that they had all been very strong readings which I would welcome in my collection today. After tracking it down for a decent price I am happy to say it sits on my shelf next to Barbirolli and Beecham and Boult once again.

Malcolm Sargent was adored by choral singers and loathed by orchestral players in equal proportion and his offhand manner and snobbish attitude towards orchestras have damaged and all but destroyed his reputation as one of the best conductors that stood in front of ensembles for over fifty years. Today, however, we can perhaps find a reason for his destructive behaviour and attribute some of his attitudes to being on the autism spectrum which was not known a century ago and grew perhaps out of the tragic death of his daughter Pamela from paralysis and his battle with tuberculosis in the 1930s.

He was the youngest person to gain a doctorate of music at nineteen and like his famous fellow conductors he was knighted in 1947 but his greatest achievements were with the large choral societies of England which dominated the musical world for millions of ordinary people who enjoyed singing together during the pre and post-war eras in industrial Britain. They kept the music alive in the northern cities of Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds during the bombing and mayhem of the second world war.

One of my teachers at college was chorus master of the Royal Choral Society for over ten years during Sargent’s tenure and whilst aware of his traits happily stated that he never worked with a better choral trainer.

Despite his clumsy relationship with orchestras, he should be praised for supporting the London Philharmonic who were left rudderless by Thomas Beecham when he left for the USA at the commencement of WW2 and also helped to support the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra when Beecham died in 1961 leaving a litany of promises that would never be fulfilled.

He was also the principal conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra for six years succeeding Sir Adrian Boult in 1950.

Listening to Sargent today I am struck by the leanness of his interpretations and the skill that he brings in drawing out detail in both singers and orchestras that almost mirror modern interpretations.

I have no hesitation in recommending the following ten recordings that demonstrate his worth as an orchestral interpreter and choral conductor and I hope that you gain as much enjoyment from them as I have done.

William Walton - Belshazzar’s Feast. James Milligan - Bass

Huddersfield Choral Society; Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

Sargent made many recordings of choral works mainly in mono during the 1950s and his recording of Belshazzar is one of his best from 1958.

Sargent made two recordings in mono of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius which both deserve attention, and he further made a stereo version of The Messiah again with Milligan, Richard Lewis and Majorie Thomas in Liverpool which is worth searching out.

Elgar - Violin Concerto. Jascha Heifetz/LSO

This performance is notable for giving a clear idea of why Sargent was a popular concerto accompanist and also shows the dazzling virtuosity of Heifetz in this most complex of concertos. Although recorded in Abbey Road in 1949 it is in good sound and worth a listen for the no-nonsense approach of both artists.

Holst - The Planets. BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Sargent made this recording in stereo in 1958 and it is very fine and gives a showcase for the talents of the BBC orchestra shortly after Sargent left them as principal conductor. I have always found this to be a clear, clean and absorbing performance which amply demonstrates Sargent at his best and with a vivid recording that was the EMI go-to for this work for many years on the Classics for Pleasure label.

Sibelius Symphonies Nos. 1 and 5. BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Sargent visited Sibelius in the early 1950s and considered him to be the foremost composer of the age. He recorded these symphonies in 1956 and 1958 in Kingsway Hall and show him to be a skilled interpreter of Sibelius, he also recorded the Karelia Suite with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1961 in the Musikverein which was the first for a British conductor since the war. [Audiophilia’s late, great Harry Curry (Harry died last year, age 91) was a member of Sargent’s Royal Choral Society while a student in London. Harry’s charm and great musicianship ingratiated him to Sargent. Over late-night drinks after gigs, Harry would regale us with Sargent stories, all of which cannot be reprinted here, including an especially racy conversation between Sargent and Sibelius during the visit Jim references!-Ed]

Sargent meets Sibelius.

Rossini - Overtures. Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

In 1960 and 1961 Sargent went to Vienna where he recorded popular works for EMI, his performance of the overtures Semiramide and The Journey to Reims gave these obscure overtures a new shine and the opportunity to polish his international credentials which flowered during the 1960s towards the end of his life.

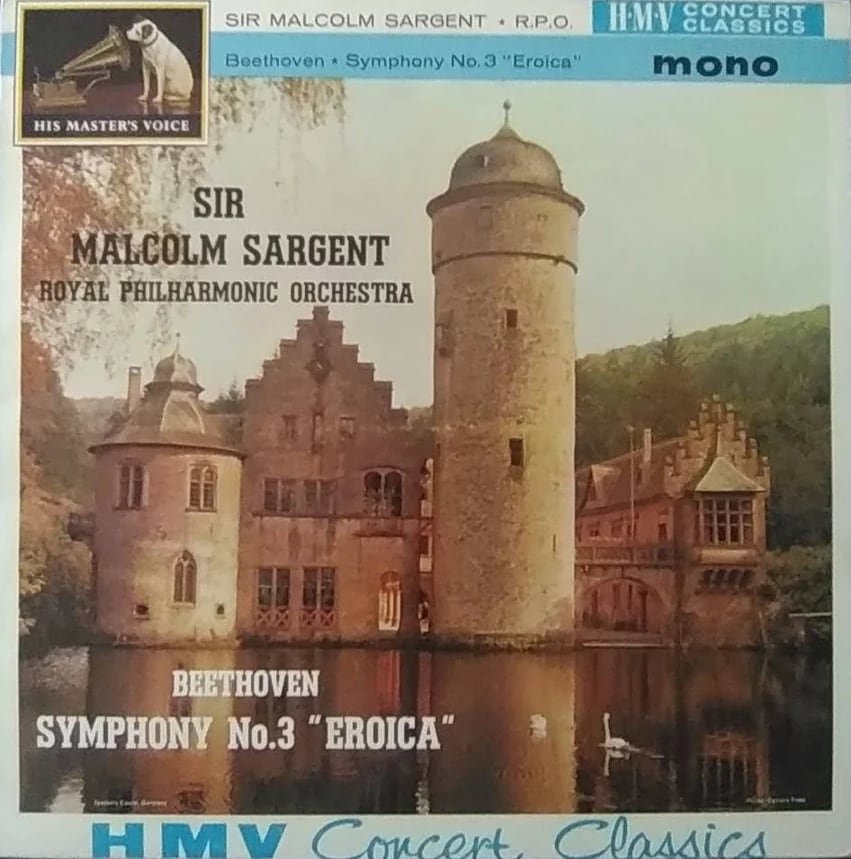

Beethoven Symphony No. 3 “ Eroica”. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

When Beecham died suddenly in early 1961, he left a number of recording plans unfulfilled and Sargent stepped in to help rescue the orchestra and keep it going until a successor to Beecham was appointed.

This allowed Sargent to record repertoire that he might not get a chance with, so we have this rather fine performance of the Eroica, which is definitely worth a listen. It again shows how Sargent applies his clean, clear demands on an orchestra and how successful the results could be.

Dvořák Concerto for Cello and Orchestra. Paul Tortelier/Philharmonia Orchestra.

Once again Sargent shows his way as an accompanist with a young Tortelier giving a passionate performance of this evergreen but sometimes underappreciated concerto.

Smetana Má vlast. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Not the most natural repertoire for a British conductor, but it is a fine performance and worth a listen. By now the RPO was back in its stride in this 1964 Abbey Road recording and Sargent secures fine playing from its list of star principals.

Walton Symphony No. 1: New Philharmonia Orchestra.

In 1966 EMI wanted to record the first symphony of William Walton with the New Philharmonia orchestra to show off its still fine pedigree, the problem was that Boult had done it with the LPO for Decca a few years earlier and Barbirolli was only interested in doing it with his Halle orchestra which EMI didn’t want to do.

Sargent was the only other choice, so he got to record this major symphony of the 20th century with the composer attending the recording.

EMI PR working overtime.

Walton did not like Sargent and was grudging in his praise for the end result but to me, it is one of the finest performances of the work and shows what an orchestra can do with a big orchestral canvas and a clear conductor in charge.

This was Sargent’s last commercial recording as he died in October 1967 and I think it is a fitting tribute to a conductor who despite his problems made a major impact on the British music scene over fifty years or more. I hope you enjoy the results.