Gustav Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde—a brief introduction

[You’ll find the author’s recommended recordings throughout the post. Texts to the songs may be found here—Ed]

Gustav Mahler and his compositions are here to stay. There are festivals, many recordings annually, books on his life and works and new chamber arrangements of his symphonies. Still, classical music lovers are hungry for more.

With gigantic symphonies, beautiful songs, not to mention his letters to famous friends (most notably Strauss and Schoenberg), and family (especially his wife Alma) have all enthralled us. Though much has been written about his compositions, they are frequently loaded with complicated explanations that obfuscate what they represent: an emotional connection to ourselves.

I believe with Mahler, we need to find the small pieces of the big puzzle and patiently experience his work. That’s what I’ve chosen to write here, a summary of a composition very dear to him, Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth, also “DLVDE”). Isn’t the entirety of his works a picture of his inner world and emotional journey? Yes, but DLVDE is even more salient, a colourful, I dare to say sorrowful picture, a painting, full of vibrant expressionism, distorted and subjective at its core.

DLVDE is a six-song symphonic composition for tenor and alto (or baritone) with orchestra. In many ways, DLVDE reiterates the expressive range of Mahler’s creativity. During a turbulent time in his life, Mahler worked to compose a song cycle based on ancient Chinese poetry. He also incorporated the pentatonic scale system (having no semitones) that gave the composition a new sounding atmosphere and engagement with its listeners. I’ll discuss what led to its creation and why this work is such an intimate composition. Furthermore, why does this oeuvre move us very differently than his other works? This is a very general explanation of the work. DLVDE is a massive piece to analyze and what follows is just the tip of the iceberg. Hopefully, it will motivate you to listen and experience.

Context of Das Lied von der Erde

I’d say that almost everyone who listens to Mahler’s compositions feels the need to express an opinion of them. If there’s a composer who brings out aversion or instant praise, it’s Mahler. Although Mahler’s live concerts haven’t rippled the waves of music history books or evoked echos of hysteria (as with the Stravinsky in Paris and Berg in Vienna), each premiere was an event. Das Lied von der Erde premiered on November 20th, 1911 in Munich on a two-day memorial concert for Mahler (there were several memorials throughout Europe) who had passed on May 18th of that year. With his faithful friend and student Bruno Walter conducting, the emotional moment for those in attendance must’ve been an unforgettable moment.

Critic, William Ritter comments on the premiere of Das Lied von der Erde (1911):

“Everything proceeded in accordance with the experience of the previous premieres. The same faithful followers, the same curiosities hastened from the four corners of the world, the same triumphal reception among the youth, the suffering, the disinherited of this world, the sincere and sensible, and the same disdainful condemnation among a portion of critics…Mahler is no more, and Bruno Walter has risen from his place in the audience to the podium. Anyone who did not witness the paleness of Bruno Walter, forced to come back a dozen times and bow to those frantic with love intermingled among sneerers full of hate, cannot convey the intensity of emotion and the stormy ardour that differentiates a Mahler premiere from any other” (from Stephen E. Hefling’s Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde).

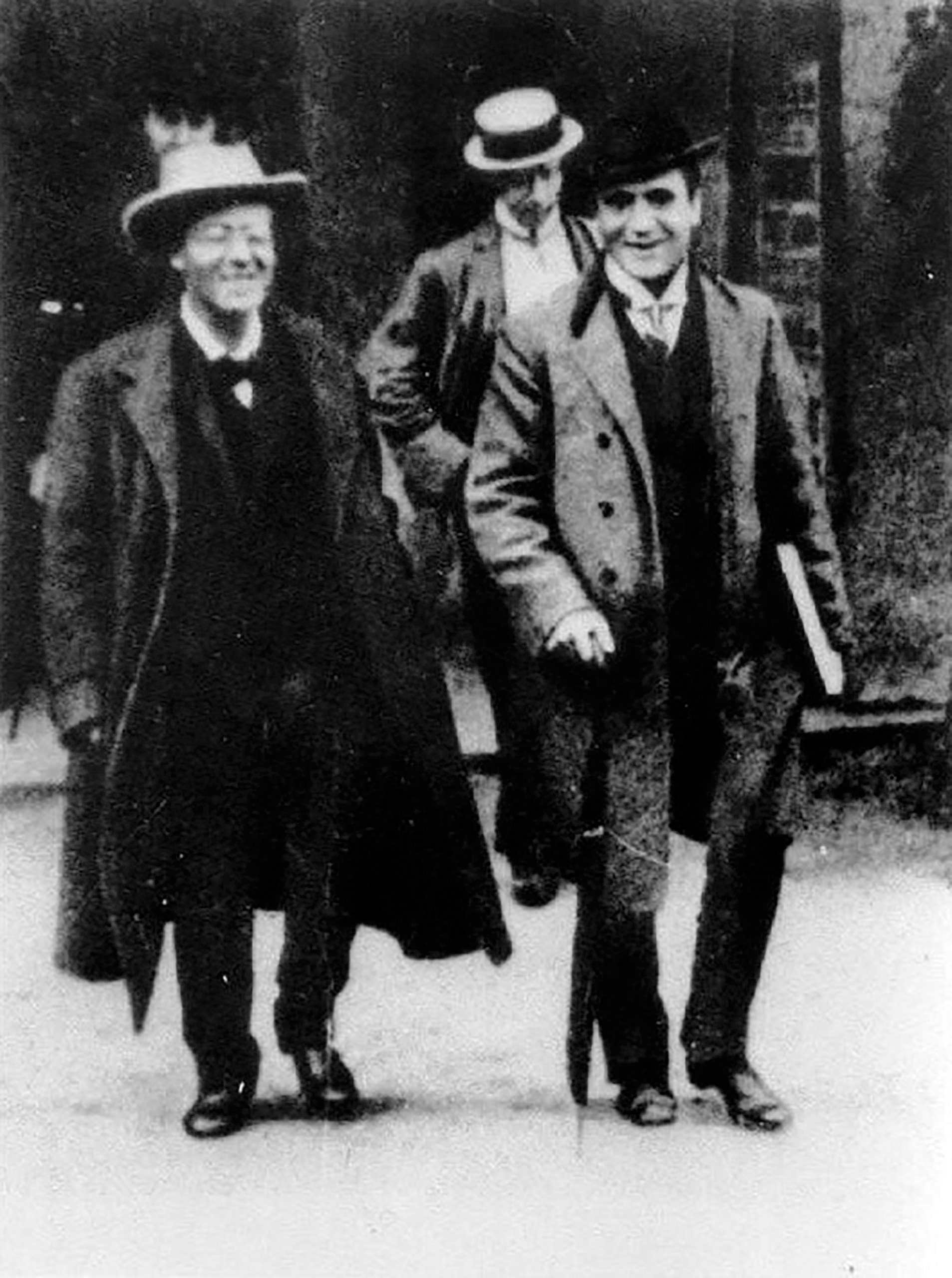

Mahler (L) walking with his friend, conductor Bruno Walter at the time of composing DLVDE in 1908. Photo credit: Mahler Foundation

DLVDE is a farewell, a disconnection, a departure from all earthly life. Through a resonating renunciation, this oeuvre weighs heavy with grief, love and despair. For some, it’s arguably Mahler’s greatest creation; he delivers an enchanting idealization of the beauties of life on earth, followed by complete resignation. In the composer’s words “The most personal thing I have ever created”.

Beginnings of Composing Das Lied

After completing his Eighth Symphony, Mahler was emotionally dazed by a myriad of events. First, his last days at the Vienna Court Opera were weighing on him. By May 1907, he had handed his resignation because of an antisemitic culture (there’s a good book that details this experience, Seeing Mahler: Music and the Language of Antisemitism in Fin-de-Siecle Vienna by K.M. Knittel). Also, the amount of work and productions he was asked to fulfill each year was outrageous. Mahler finally decided to end his relationship with the Vienna Opera; he negotiated (while in Berlin) with Heinrich Conried (the Metropolitan Opera manager) a contract that would take him for four years to New York, with relatively less stress for the Austrian (only three working months per year) to begin in November of 1907.

My favourite Das Lied recording is with Kathleen Ferrier, Julius Patzak, Bruno Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic from 1952. Maybe not the best, but Ferrier’s angelic voice moves me profoundly.

Before he could set his mind to ponder a new job, in a new country and mourn the loss of his beloved Vienna Opera, in July 1907, Mahler suffered a terrible blow—Maria Anna his four-year-old daughter, died on July 12th, having fallen ill of diphtheria. The pain of losing “Putzi” never really left Mahler and he even chose to be buried in her grave. This event was devastating for Mahler.

Alma comments:

“She was his child. Marvellously beautiful and obstinate, at the same time unapproachable, she promised to become dangerous. Black curls, big blue eyes!” […] Though it was not granted to her to live a long life, she was chosen to have been his joy for a few years, and that in itself has eternal value.”

If these nightmarish episodes weren’t enough, the family physician Dr. Blumenthal, who was summoned when Alma had fallen unconscious (after Putzi’s coffin was taken from their home), examined Mahler’s health and concluded the composer had an issue with his heart. Later, a specialist (Dr. Kovacs), confirmed it as a “Compensated heart valve defect with narrowing of the mitral valve opening; hence all bodily exertion must be avoided starting immediately” (from Anton Neumayr’s book: Music and Medicine, Chopin, Smetana, Tchaikovsky, Mahler: notes on their lives, works and medical histories, 1997).

Mahler’s daily routine and perhaps musical inspiration came during his outdoor activities. Mahler enjoyed nature; its sounds and wonder were crucial in his life. The exercise was an important part of who he was since he was a young man. Having to avoid these activities left him feeling dismayed and anxious.

Considered by many to be the best recording/performance is Klemperer’s EMI Das Lied with Christa Ludwig, Fritz Wunderlich and the New Philharmonia Orchestra (1964/1966).

Das Lied von der Erde was composed with these emotionally draining events in mind. Mahler and his family needed a pause so they left their home in Maiernigg (Carinthia, Austria) for the Tyrol (northern Italian border with Austria) to work. It was here he returned to reading a book, Hans Bethge’s Anthology Die chinesische Flöte. A translation from a collection of poems of the Eighth century A.D. Tang Dynasty. Bethge’s anthology was in fact a summary of other authors: Léon d’Hervey de Saint-Denys ‘Poésies de l’époque des Thang’, Judith Gautier ‘Livre de Jade’, Hans Heilman ‘Chinesischer Lyrik’. The Chinese poets included in the anthology were Li-Bai, Qian-Qi, Mong Koa Yen and Wang-Wei. Interestingly for Mahler, nature, the journeyman or wonderer, beauty and death, were central to their poetry. Suffice it to say Mahler was intrigued. Mahler used seven poems for the six songs in DLVDE.

The Six Songs

The work was completed in September 1908. It was not his intent to number it his Ninth Symphony for the superstitious belief that “No great composer lives to create after his Ninth”. He first thought of calling the symphony Das Lied vom Jammer der Erde (The Song of the Misery of the Earth), but he settled on Das Lied von der Erde because according to his friend Richard Specht, Mahler was emotionally drained and felt that a farewell described more clearly his experience. Having already incorporated song in his Second, Third, Fourth and Eighth symphonies, Mahler had finally achieved a completed symphony of songs, elegant in their musical detail, but marked with a devastating experience in its emotional and lyrical meaning.

The original Universal Edition score. Notice the title, Eine Symphonie? “A Symphony for Tenor, Alto and Large Orchestra”.

Song I. Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde / The Drinking Song of the Misery of the Earth (by Li-Bai).

In this first song “Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde”, the singer/speaker has an audience, he constantly searches for meaning in contemplation, he invites others to listen, he sings a song of sorrow commenting on how “Life is dark, and so is death!”

A draining and dark gloom hovers over the music, a voice ruptures the self, a pure Mahler creation. The poem describes the emotional state of being from the drinking poet. What is life? “Joy and song fade and die” he sings. The music enthralls us with its pentatonic themes. Here nature and primitive self complement the sound of Mahler’s creation in the form of an ape crying under the moon on a tomb, reaching a climax with the orchestra playing ascending phrases. Horn calls rapture the scene as the speaker and his sorrow continue. Wine again soothes. Deryck Cooke (Gustav Mahler An Introduction to His Music, 1988) comments on this first song: “A furious defiance of grief, which keeps falling into a shadowy subsidiary theme. There is an exquisite central orchestral section, a shimmering vision of earth’s beauty”.

Song II: Der Einsame im Herbst / The Lonely One in Autumn (by Qian-Qi).

If we encountered pondering life in the first song, suffering is the tale of this second song. A more intimate chamber-like feel, nature again, with lakes, grass and the cold, vanishing scents of flowers expose loneliness and a melancholic self in the alto/baritone.

An oboe develops a sense of failure and sadness, a voice that fuses with violins, with contemplation turning into a soliloquy of what has gone and perhaps will never return. A fatigue of sorts sets in, and climactic moments with wind-like sounds all around make this a beautiful song. Analysis of pain and inner struggle find an anchor here and lingers like the oboe which ends the piece, soothing in lament.

Song 3: Song III: Von der Jugend / Of Youth (by Li-Bai).

“Of Youth” shocks us with the first contradiction of the work. No suffering days of autumn here. It’s a party of poets in a pavilion, with a pool! The singer experiences a beautiful moment around friends. Even Theodor Adorno (Mahler: A Musical Physiognomy, 1996) found it surprisingly cheerful: “Directly with tangible connections through motives, the world of Chinese imagery of Das Lied von der Erde is derived from the biblical Palestine of the Faust music, particularly in the outwardly most cheerful song ‘Von Der Jugend’”.

If you want a baritone, Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau (in his prime) with Murray Dickie (tenor) and the Philharmonia Orchestra under the baton of Paul Kletzki (1959).

The tenor finds his way with woodwind instruments that become a resonating echo of fun. In a joyful episode, he gazed at a pool and leaves his friends a moment to contemplate his inner self. This very brief event (the shortest song) and its brisk tempo almost make us believe in happiness. The rhythm here is used to flow with the grooves of the party, so to speak. Those short bursts of woodwinds and bells, sound like energetic phrases that invite us to sing, laugh or even dance. When the singer stares at the pool a shift in retrospect of where he is set in: “Everything stands on its head in the pavilion of green and white porcelain. Like half-moon the bridge stands, its arch inverted. Friends. Beautifully dressed, drink, chat.” A rare tale of happiness in Mahler’s work indeed.

Song IV: Von der Schönheit / Of Beauty (by Li-Bai)

A love story of a girl who falls in love with a young boy on a horse. Some romanticism showing off here. Youth and beauty along with desire. One girl’s love and loss, perhaps her first intimate encounter with love, follows a legato that fills the music. In the first scene, the girl is picking lotus flowers from a river. The sun shines and water captures the girl’s reflections, the wind carries her perfume. Youth is here punctuated along with the accompanying woodwind timbres in the opening theme. Love silences one girl’s inner world.

What begins with a joyful and festive sound (G major pentatonic theme) turns into a more exciting and faster tempo. A frenzy ends and tension builds preparing us for the next moment, a boy’s arrival on a horse. His energy is palpable, he and his horse are vigorously riding away. The horse’s hooves crushing fallen blossoms invite our interpretation of the passion in the girl, the “fairest of the maidens” her gaze and heart “throbs”. Or perhaps, what is crushed is the girl’s heart, who is left with her desire and unrequited love. That theme of loss again.

Song V: Der Trunkene im Fruhling / The Drunk Man in Spring (by Li-Bai)

While the alto loves, the tenor laments. This song brings us back to the misfortunes of the poet’s life. Here we have the second scherzo (horn theme beginning) of DLVDE. Disappointed in the world, he drinks all day “I drink until I can drink no more” followed by “soundly” sleep. Woodwind instrument bird calls are Mahler’s superpower. A bird (piccolo and oboe) begins a conversation with the poet, “Spring is here, it came overnight”. The pessimistic drunk for a moment listens to the bird but then goes back again to his despair “Let me be drunk”.

We are now ready for the last song, a composition that rivals any other of Mahler’s creations as the most beautiful and haunting.

Song VI: Der Abschied / The Farewell (by Mong Koa Yen and Wang-Wei)

“Der Abschied", is for me (perhaps along with the Adagio from Mahler’s Ninth) the most beautiful and painful composition I’ve ever listened to. This movement embodies being and the eternal. What makes this movement otherworldly? It’s the longest movement (around 30 minutes). A hypnotic mantra (Ewig / For ever) hovers over the entire piece. Mahler uses everything in his arsenal from bird calls and low drone sounds (horns, tam-tam, cellos harps) to major-minor shifts. As Sidney Sun tells us “The lack of tonal resolution reflects the poem’s opening ending and the world’s eternity” (in the thesis Gustav Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde: An intellectual journey Across Cultures and Beyond life and Death, 2009).

The singer begins in recitative—the loneliness is palpable. In the first moments, nature becomes a faithful partner to the alto. The singer reflects on nightfall, mountains, the moon, the breeze, and the twilight glow is felt. Alone, waiting for a final farewell from a friend. There’s an almost motionless melody at the beginning and the plucking of string instruments reminds us of a needed pause for thought, contrasting with long phrases that go back and forth, complementing the vocal journey. Here Mahler is setting the tone for what’s to come.

“My friend, fortune was not kind to me in this world. Where am I going? I go to wonder in the mountains”.

This painful moment arrives with the change in the music of course. “Der Abschied”, this marvellous composition tests our belief in the philosophical other, in the limits of love and friendship. In the end, free from the world, and into nature. The last word Ewig is what we hear seven times in the final measures. The song-symphony ends with a transcendental air.

David Zinman conductor, Susan Graham and Christian Elsner with the Tonhalle Orchester Zurich (2012).

Conclusion

So then, it has come to this, we start our life alone, we find friends, we love a partner, but then there’s a farewell, in solitude. Mahler is the greatest composer of subjectivity. He composed how the self experiences emotions and being. We have other composers for spirituality (Bach), for the other (Beethoven), but for the self, alone in its subjective nature, we have Mahler.

Perhaps this is the work’s task, an invitation to let go of earthly life, through compulsion, love, friendship, innocence and finally death. Mahler has a way of exposing us, he pulls our emotional strings with such ease, that listening to a complete symphony or song-symphony sends us into an unrequested mind labyrinth. Explore, experience and live these current moments of sorrow, with the beauty of music, the way I imagine Mahler did.